by Jedi Reign

Hair and the styles it is put into represent more than something to compliment the day’s outfit, especially for the African and African American community. Centuries of slavery stripped 7 to 8 million people of their culture and family history while “depriving the African continent of some of its healthiest and ablest men and women” (History Editors). However, one thing that has continued to stand as a point of unity and value for black people is their hair. This essay will focus on the cultural significance of specific African hairstyles known as Box Braids, Dreadlocks, Cornrows, and Bantu Knots in Africa and the United States while acknowledging their presence in American fashion through cultural appropriation.

Check out Jedi Reign’s Natural Hair Journey.

HISTORY OF CORNROWS

The beginning of cornrows dates back to 3000 B.C. or Ancient Egyptian times (Gabbara). This popular African hairstyle is made by taking three strands of hair and braiding them to the scalp. With each woven piece, the braider grabs a little more hair that isn’t in the strand to make it as tight as they desire. In Africa, cornrows show a person’s “marital status, age, religion, ethnic identity, wealth, tribal rank, fertility, manhood or warrior status, and even death or mourning (Ellington 1). Before slavery, cornrows meant even more to the African culture than they do today.

The ability to cornrow was considered sacred, so the eldest female taught the younger females how to do it. Men also taught hair braiding to eliminate hair braiding of the opposite sex. This tradition continued for generations. Braiding each other’s hair was a spiritual ritual that helped strengthen and build relationships between family and friends. Bedraggled hair let society know that person was morning, mentally ill, or a social outcast. In turn, everyone wanted tamed and neat hair, so to get this look, they braided their hair into cornrows. Braided hair was also used to attend special occasions and to attract a companion (Ellington 2). However, as many people were forced to leave the African continent, the cultural meaning behind cornrows began to change.

The name “cornrow” originated in America during slavery. They mimicked the land they worked on by braiding that pattern into their hair. Africans and African Americans used combs that also looked like the tools they used on the land to part their hair. Thus, the beginning of the name cornrow. This type of hair braiding has more than one name. Caribbean slaves used the name “canerows” because they mimicked the cane fields they were forced to work on. In America, white people made it their mission to “strip away their heritage” (Ellington 2). To do this, they made the slaves shave their heads (Johnson). So, the cornrow had important meanings to the people in America, but not the same or as essential as Africa’s original connotation. Slaves also used braids to hide rice and seeds so they would have something to eat. The braiding style also communicated to other slaves that they needed something or were going to run away (“More Than a Hairstyle”).

After slavery was abolished, African Americans wanted to look like their white counterparts, so they straightened their hair. By 1948, “all signs of cornrows and braids diminished” (Ellington 3). However, this didn’t last forever because, by the 1950s-1960s, black people created the black panthers and the civil rights movement. They began embracing their culture and their hair again while dismissing the beauty standards society forced on them. By 1990, cornrows grew ever more popular, and an “emphasis was placed on creating cornrows with the wearer’s natural hair,” unlike box braids (Ellington 4). Celebrities known for wearing this style included Alicia Keys, Venus and Serena Williams, Snoop Dogg, Lil Bow Wow, and Ludacris.

HISTORY OF BOX BRAIDS

Like cornrows, box braids are another flourishing hairstyle that takes root in Africa. First known as Eembuvi braids or bob braids, box braids originated in Egypt around 3500 B.C. (Muhammad). They are made by three-strand braiding synthetic or human hair into someone’s real hair to add thickness and length. Jewels, shells, and beads were added to the braids to show that person’s “readiness to mate, emulation of wealth, high priesthood, and various other classifications” (Gabbara). Getting box braids done showed a great deal of wealth and patience as it takes hours to get them done, and the materials were not cheap. Box braiding was used mostly by Africa’s southern region, specifically, the Mbalantu tribe of Namibia. It was a way to identify different tribes and their unique braiding styles. Like the tradition of learning cornrows, the eldest women would teach the children how to braid. This tradition kept the community strong and created bonds between the people (Nxumalo).

Box braids gained popularity in the United States in the 1990s (Allen). According to Ebony, a new source on African American culture stated that Janet Jackson inspired an obsession with the hairstyle with her film debut, Poetic Justice. Women of the black community wanted box braids to wear them just like Janet did in her video. Brandy, another prominent singer in the African American community, also contributed to the “new” trend by “experimenting with shorter lengths, thickness, styles (i.e., pigtails), and colorful hair clips and scrunchies (Gabbara). They showed the black community that they could be successful while embracing hairstyles handed down by their ancestors.

HISTORY OF DREADLOCKS

Dreadlocks were created around 2,500 BCE. Archaeologists have recovered mummies with their locs. They’ve also found that “ancient Egyptian pharaohs wore locs, which appeared on tomb carvings, drawings, and other artifacts” (Gabbara). Many other civilizations have connections with dreadlocks as well. They represent a way for people to connect with their spiritual beliefs. Where the name dreadlock came from isn’t entirely known. Bine, a writer for the DreadFactory, believes the name came from the Rastafari Movement, a religious and spiritual movement in Jamaica. Locs are “an important religious symbol and connects the wearer with their God Jah, representing deep respect for the deity” (BINE).

Along with the plethora of communities that wear dreadlocks, there are several ways to create them. However, the most common/modernized way is taking the hair by the root and twisting it with a comb to form a twist or a coil. It takes up to two years to get the full “loc” look. At that point, the dreads are considered mature because they are completely locked (Gabbara).

Bob Marley popularized dreadlocks in the United States in the 1970s. As his music grew, so did the number of people noticing his hair. In the 1980s, Whoopi Goldberg furthered dreadlock’s popularity. Soon other celebrities like Lauryn Hill and Lenny Kravitz wore the hairstyle as well (Gabbara). The natural hair movement also encouraged others in the black community to embrace locs. People were comfortable wearing their hair in its natural state and using styles to protect its health and length. Today, dreadlocks have the most connection with Jamaica even though they didn’t originate there. To many, wearing dreads is more than a hairstyle; it is accepting a religious way of life.

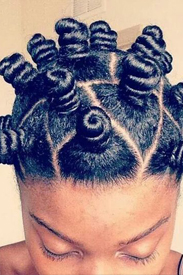

HISTORY OF BANTU KNOTS

Bantu Knots were first discovered in 1898 (Gabbara). They are made by sectioning off the hair and twisting each section into individual balls or knots. The word Bantu is a “comprehensive term used to describe 300-600 ethnic groups within southern Africa that spoke the Bantu language” (Tipton). They created the Bantu knot, and they are used as a protective style to moisturize and define curls. Bantu knots are also referred to as Zulu knots by the Zulu people.

Bantu Knots are very popular with African Americans today and the fashion industry. Celebrities like Blac Chyna, Rihanna, Halle Berry, Jada Pinkett Smith, and Beyonce have been spotted wearing knots on red carpets and in music videos (“BANTU KNOTS”). Knots are mostly worn by women who take pride in their African roots.

CULTURAL APPROPRIATION

Cornrows, Box Braids, Dreadlocks, and Bantu Knots are seen everywhere in the African and African American communities. After centuries of disconnect and racism, African Americans were able to keep up with the history and style behind the hairstyles. Nonetheless, black people are continually told that their hair needs to change because it doesn’t meet the European standard of beauty. Now, “racism has shifted from overt forms of outright discrimination to more ambiguous expressions and behaviors against those oppressed” (Ellington 4). African American’s natural hair is often described as dirty, unprofessional, thuggish, and nappy hair that needs to be “tamed” (Griffin). Corporations and businesses like American Airlines and the Hyatt Regency have a history of demanding black women to alter their hair from its natural state. Refusal to comply can lead to women being forced to resign or them being fired from their job. Even the United States army court-martialed a woman in 1975 for wearing cornrows because the hairstyle was “outlandish” (Ellington 4). A famous line from Regina Kimbell’s film, My Nappy Roots: A Journey Through Black Hair-itage, states that “if your hair is relaxed, they are relaxed. If your hair is nappy, they are not happy” (Griffin). America pays the most attention to black people when they do not follow their societal norms, especially regarding their hair.

Even though black people are ridiculed for wearing their natural hairstyles, white American men and women have no problem wearing them to be “fashionable” or exotic.” Cultural Appropriation is when a dominant group claims certain items, traditions, or cultural aspects of a minority group and claims it as their own (Grays 2). White people started wearing cornrows in the 1970s. Actress Bo Derek wore cornrows with beads in the movie 10. White women then wanted to wear the new “Bo Braids” to be just like her (Ellington 5). In 2016, Kylie Jenner posted a picture on Instagram captioned “I woke up like disss” while wearing slick back cornrows. She received backlash from the African American community because she wore a hairstyle that had very special meanings associated with it as an accessory. She was also allowing people outside of the community to believe that it was a hairstyle “available to everyone” (Grays 4). These women received acclaim for hairstyles black women have to fight to wear whenever they want.

White male celebrities have also worn and appropriated black hairstyles. In 2016, Justin Bieber went to the iHeartRadio Music awards wearing dreads. He responded to the criticism by saying that “it’s just my hair” (McDermott). This didn’t go over well with the fans because in 2015, Zendaya wore dreadlocks to the red carpet and American-Italian reporter Giuliana Rancic said that her hair looked like it “smells like patchouli oil…or weed” (McDermott). In 2018, Zac Efron posted a picture of him wearing dreadlocks on Instagram with a caption that said: “just for fun” (France). Other white celebrities caught appropriating black hairstyles include Marc Jacobs in 2015, sending white models down the runway wearing Bantu knots but calling them “twisted mini buns” (Oliver). In 2016, Khloe Kardashian posted a picture on Instagram with her wearing Bantu knots and originally captioned it “Bantu Babe” before she changed it to say, “I like this one better” (Bryant). Lastly, in 2016 Vanessa Hudgens posted pictures of her on her Snapchat while wearing box braids. She captioned the photo “Yaaas braids” (Prakash). There are many more examples of white celebrities making African hairstyles fashionable merely because they are wearing it. While white people get to dabble with these hairstyles when they want, “many African Americans [are] forced to choose between embracing their identities and economic advancement” (Griffin).

Each of the hairstyles mentioned in this essay has an important significance to the African and African American communities. They have managed to re-embrace their culture after many outside forces tried to take it away from them. Africans and African Americas still face issues as white America pressures them to conform to their standards while wearing the very hairstyles they tell them they cannot wear. That hasn’t stopped the community from loving their hair and remembering what their ancestors intended for the hairstyles. Like mentioned earlier, in Africa, hairstyles were meant to teach the young and keep the communities together. African Americans are working against hate and working toward bringing back the normalcy that comes with them wearing their natural hair. Cornrows, Box Braids, Dreadlocks, and Bantu Knots are becoming an outward manifestation of [their] love and acceptance for [themselves] (Gabbara).

Works Cited

Allen,Maya. “The Fascinating History of Braids You Never Knew About”. BYRDIE, 24 October 2019, https://www.byrdie.com/history-of-braids

“BANTU KNOTS- 8 BLACK CELEBRITIES THAT PROVE THIS STYLE IS BOMB”. 1966 Magazine, 6 October 2015, https://1966mag.com/bantu-knots-8-black-celebrities-that-prove-this-style-is-bomb/

BINE. “A short History of Dreadlocks”. DreadFactory, 9 July 2018, https://dreadfactory.de/en/2018/07/09/a-short-history-of-dreadlocks/

Bryant, Taylor. “ Khloé Kardashian Is Being Called Out For Cultural Appropriation”. Refinery 29, 15 August 2016, https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2016/08/120157/khloe-kardashian-bantu-knots-cultural-appropriation

Ellington, Tameka. “Cornrows”. Academia. https://www.academia.edu/33401412/cornrows_pdf

France,Lisa R., “Zac Efron’s dreadlocks stir debate” CNN, 9 July 2018, https://www.cnn.com/2018/07/06/entertainment/zac-efron-dreadlocks/index.html

Gabbara, Princess. “Cornrows and Sisterlocks and Their Long History”. EBONY, 20 January 2017, https://www.ebony.com/style/everything-you-need-know-about-cornrows/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CHistory%20tells%20us%20cornrows%20originated%20in%20Africa.&text=%E2%80%9CCornrows%20on%20women%20date%20back,identified%20by%20their%20braided%20hairstyles.%E2%80%9Dhttps://www.ebony.com/style/everything-you-need-know-about-cornrows/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CHistory%20tells%20us%20cornrows%20originated%20in%20Africa.&text=%E2%80%9CCornrows%20on%20women%20date%20back,identified%20by%20their%20braided%20hairstyles.%E2%80%9D

Gabbara, Princess. “Everything You Need to Know About Bantu Knots”. EBONY, 29 November 2016, https://www.ebony.com/style/everything-you-need-know-about-bantu-knots/#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20hairstyle%20can%20be,back%20to%20at%20least%201898.&text=%E2%80%9CBantu%E2%80%9D%20is%20a%20blanket%20term,ethnic%20groups%20within%20southern%20Africa

Gabbara, Princess. “ The History of Dreadlocks”. EBONY, 18 October 2016, https://www.ebony.com/style/history-dreadlocks/

Gabbara, Princess. “The History of Box Braids”. EBONY. 24 August 2020, https://www.ebony.com/style/history-box-braids/

Grays, Jaja. “The Blurred Lines of Cultural Appropriation”. City University of New York, 16 December 2016, https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1193&context=gj_etds

Griffin, Chanté. “How Natural Black Hair at Work Became a Civil Rights Issue”. Jstor Daily, 3 July 2019, https://daily.jstor.org/how-natural-black-hair-at-work-became-a-civil-rights-issue/

History Editors. “Slavery in America”. History.com, 12 November 2009,https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery

Johnson, Tabora A., Bankhead, Teiahsha. “Hair It Is: Examining the Experiences of Black Women with Natural Hair”. January 2014, file:///Users/jediahholman/Downloads/Hair_It_Is_Examining_the_Experiences_of_Black_Wome.pdf

McDermott, Maeve. “Here’s why people are mad about Justin Bieber’s dreads”. USA Today, 4 April 2016, https://www.usatoday.com/story/life/entertainthis/2016/04/04/justin-bieber-dreads-controversy-iheartradio-awards/82613286/

“More Than A Hairstyle: How Braids Were Used To Keep Our Ancestors Alive”. Blackdoctor.org, https://blackdoctor.org/history-of-african-hair-braiding/2/

Muhammad, Tia. “6 POPULAR BRAIDING STYLES & THEIR TRUE ORIGIN”. ONCHEK.com, https://www.onchek.com/theinsight/6-popular-braiding-styles-their-true-origin/

Nxumalo, Lethabo. “YOUR ALL-YOU-NEED-GUIDE ON HOW TO DO BOX BRAIDS”. Black Hair Spot, https://blackhairspot.com/blog/hair-talk/how-to-box-braids/

Oliver, Dana. “These Are Bantu Knots, Not ‘Mini Buns.’ There’s A Difference.” Huffington Post, 6 December 2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/bantu-knots-mini-buns-difference_n_7452532

Prakash, Neha. “Vanessa Hudgens’s Box Braids Called Out for Cultural Appropriation”. Allure, 24 October 2016, https://www.allure.com/story/vanessa-hudgens-braids-hairstyle

Tipton, Kiana. “The History of Bantu Knots”. NaturallyCurly, 28 September 2018, https://www.naturallycurly.com/curlreading/hairstyles/the-history-of-bantu-knots